This summer we visited the Annecy International Animated Film Festival to get ourselves up to speed on the latest trends in animated film in this year’s competition and to dive into the history of animation in wonderfully curated film programmes such as the programme on this year’s guest country China curated by Marie-Claire Kuo-Quiquemelle of the Centre de Documentation sur le Cinéma Chinois (CDCC) in Paris . The programme took the visitor by the hand from the very first Chinese animated feature Princess Iron Fan (Laiming & Guchan Wan, 1941), throughout the turmoil of the cultural revolution and its aftermath until contemporary Chinese animation which proved to be firmly rooted in the rich traditions of Chinese art and literature, yet often critical towards the country’s social and economic politics. Throughout the history of Chinese animated film, the use of traditional, Chinese materials and techniques such as ink wash drawings, intricate paper cut techniques and even porcelain (!) has played an important role. With exeptionally beautiful results.

Grinding, tinkling and ticking porcelain

Parallel to the screening programma, ran an exhibition on Chinese animation entitled China, Art in Motion. The exhibition gave a concise overview of the history of Chinese animation, but soon moved on to the next generation of Chinese animators, presenting films, film installations and artwork by filmmakers such as Sun Xun, Haiyang Wang, Wu Chao, Weilun Xia an Xue Geng; animators working at the intersection of contemporary art and animation. One of the first things we noticed when walking through the exhibition was the materiality of some of the animations; the materials used in the animation process were almost tangible in the film. A beautiful example is the film Mr. Sea by Xue Geng, a stop-motion animation film almost entirely made out of porcelain giving the puppets a mysterious, otherworldy feel: cool and aloof, godlike almost. You can hear the porcelain grinding, tinkling and ticking, which creates a feeling of anxiety and suspense. Porcelain carries a long history in Chinese culture and is heavy with symbolism. The Chinese feel of the film is unmistakable.

Trailer for Mr. Sea (Hai Gongzi ) by Xue Geng. The story is an adaptation from the short story Killing the Serpent taken from a collection of supernatural tales entitled Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio (LiaoZhai ZhiYi) written by Pu SongLing (1640-1715). In Mr. Sea a young explorer reaches the shores of an eerie Island where he falls in a spiral of passion and death…

The aesthetics of empty space and striking brush strokes

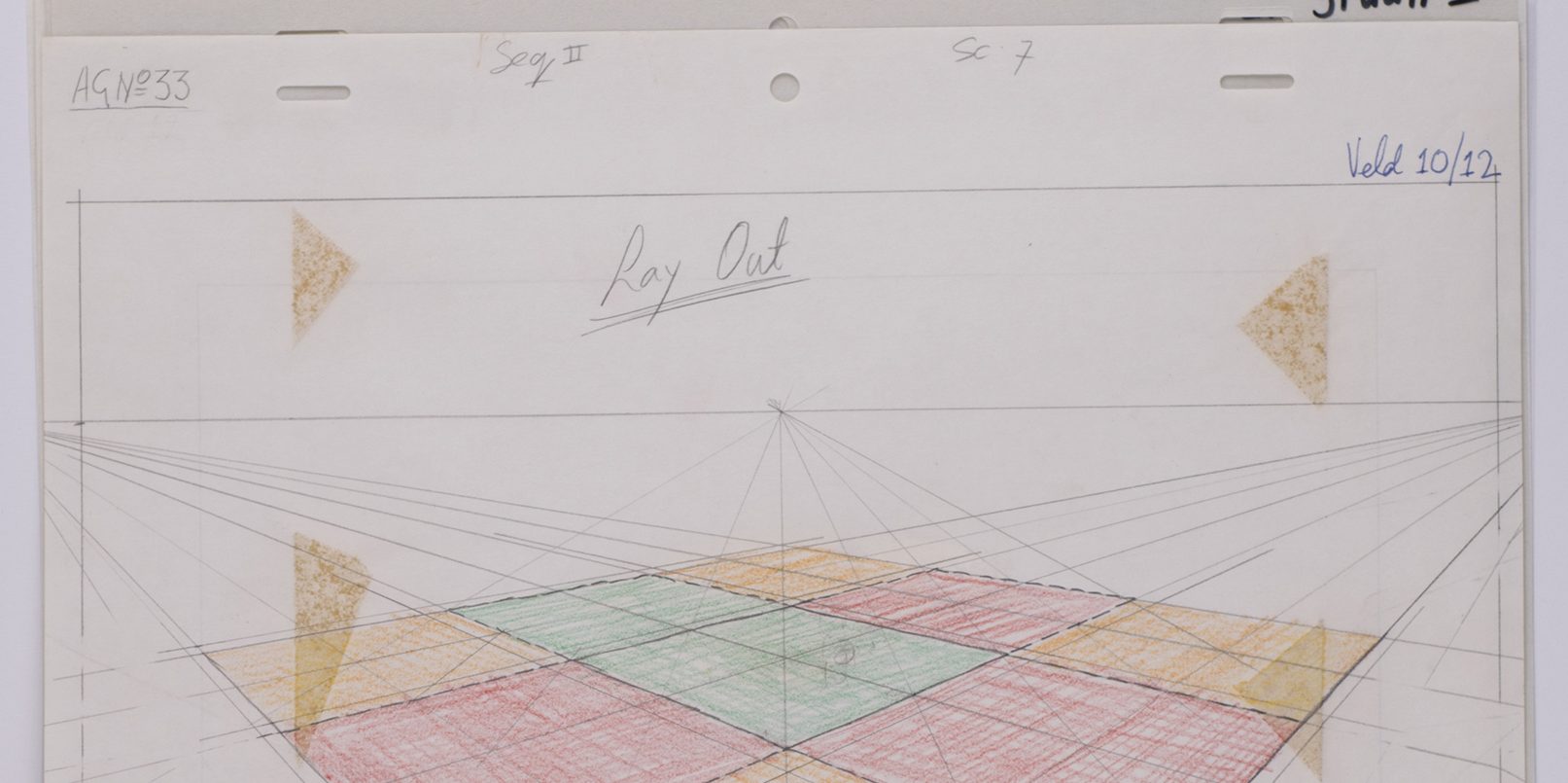

This strong connection to traditional techniques in Chinese animation has a long tradition and is especially populair during the Great Leap Forward in the years before the Cultural Revolution. Chinese animation studio’s produced intricate paper cut animation (Jianzhi), stop-motion animation using origami techniques (Zehzhi) and ink wash animation (Shui-mo). The latter style combines the animation techniques of the time with the aesthetics of traditional Chinese ink wash painting following the work of Qi Baishi in which empty space is used to convey substance and striking brush strokes are used to depict motion. Shui-mo animation first appeared in 1961 in Where is Mama?, a children’s film about tadpoles looking for their mother. Qian Jiajun brought this technique to absolute perfection in his enchanting film The Cowboy’s Flute (1963). Both films were produced by the Shanghai Animation Studio which was founded in 1958 with government funding and the special assignment to encourage the use of traditional Chinese techniques.

A still from the film Where is Mama?

Shanghai Animation Film Studio

Director: Te Wei

China, 1962

The Cowboy’s Flute (Mu Di)

Shanghai Animation Film Studio

directed by: Te Wei, Qian Jiajun

China, 1963

20′

Cuddly Animals

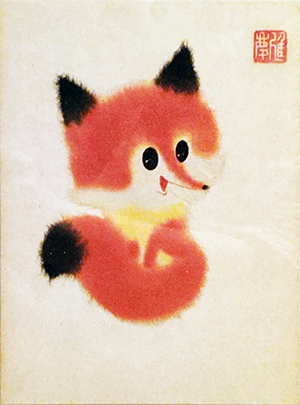

A special branch of Shui-mo animation is a technique of cut-out animation or rather “tear-out animation”: the animator paints the characters on fibrous Japanese paper with washed ink. Subsequently, he traces their contours with a brush saturated with water so he can tear the characters out of the paper. Tearing Japanese paper along a water line results in a fibrous edge that gives the illusion of a soft furry coat. This effect was especially popular in the early sixties in the Shanghai Animation Film Studio where animators such as Hu Jinqing used it to create the soft, cuddly animals that stole the hearts of millions of Chinese toddlers and their parents. An example is the little bright red fox in Le renard des neiges (produced in 1998), which is Hu Jinqing’s last film and one of the last in its genre.

Artwork created by Hu Jinqin as shown in te exhibition China, Art in Motion in the Chateau d’Annecy

The cuddly, furry look is created by tearing fibrous Japanese paper along a water line)

Toute l’actu Cinéma est sur Commeaucinema.com

Le petit singe turbulent (Taoqide jinsi hou)

Shanghai Animation Film Studio

Hu Jinqing

China (1982)

19′

Ink wash animation is time consuming and costly. Eventually it had to make way for cheaper production methods of computer animation. But, although no longer practiced, Shui-mo animation continues to inspire contemporary animators. John Stevenson, the director of the Hollywood blockbuster feature Kung FU Panda (2008), for example, said he was amazed by The Cowboy’s Flute and believed that his film should reflect this unique feature of Chinese animation. As a result, Kung Fu Panda has a computer created, stylized ink-wash background remotely reminiscent of traditional Shui-mo animation:

Spelling error report

The following text will be sent to our editors: